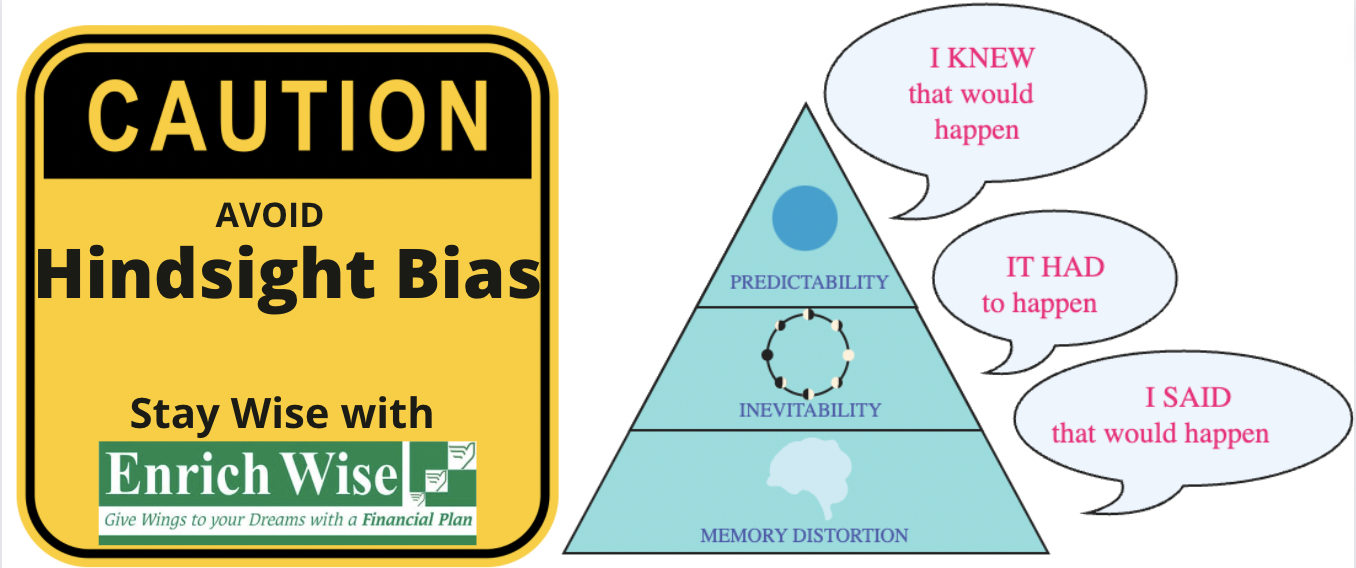

For example, if we believe that a result was practically impossible, we are less likely to be victims of hindsight bias. Surprise also influences the way we reconstruct pre-outcome predictions. When “serious injuries” were mentioned, people were more likely to rate the therapist as negligent and said the attack was more predictable. They were then asked to determine the level of negligence of the therapist. However, the therapist did not warn that person of the danger that he could be in.Įach participant was given three possible outcomes: the person in distress was not injured, was slightly injured, or seriously injured. In this sense, an example of hindsight bias occurred in 1996 when LaBine proposed a scenario in which a psychiatric patient had told a therapist that he was contemplating harming another person. A study conducted at the University of Texas found that hindsight bias is more common when the outcome of an event is negative rather than positive, demonstrating our tendency to pay more attention to negative event outcomes than positive ones.įurthermore, the more severe the negative results, the more intense that bias. There are different factors that can increase or minimize our tendency to think that we already knew what was going to happen. What makes us think that we knew what was going to happen? What happens is that current knowledge generates a false memory that makes us think that we knew what was going to happen, when in reality it was not. In practice, once we know the final result, we modify our memory to think that we knew what was going to happen, as if we were some kind of Nostradamus. Also called creeping determinism, it is the tendency to think that past events were more predictable than they actually were.Īfter an event occurs, we think we could have predicted it, or we believe that we knew the results with a high degree of certainty before it occurred. It is a cognitive bias that occurs when we know what has happened but we modify our memories of the previous opinion in favor of the final result.

Thus arose the concept of hindsight bias, also knew-it-all-along-phenomenon or creeping detrminism. Thus he found that people tend to assign a higher probability of occurrence to whatever result they have been told to be true. Then he asked them to assign a probability for each particular outcome. That same year, Fischhoff conducted another experiment in which he gave people a short story with four possible outcomes, but indicated in advance that one of them was true. In other words, people tended to think that they knew what was going to happen, although they did not. They found that they overestimated the probabilities for the events that had occurred and downplayed the rest. Some time after President Nixon returned, those same people were asked to recall or reconstruct the probabilities they had assigned to each outcome. In the mid-1970s, researchers Beyth and Fischhoff conducted a very interesting experiment in which they asked participants to judge the probability that certain results would occur before Richard Nixon traveled to Beijing and Moscow. Historians are also prone to this bias when describing the outcome of a battle and even judges are not save when they judge a case as they think that both the accused and the victim could have foreseen in a certain way what was going to happen. Doctors, for example, often overestimate their ability to have foreseen the outcome of a case and claim to have known it from the start.

HINDSIGHT BIAS PROFESSIONAL

This hindsight bias also extends to the professional area.

In fact, it doesn’t just happen to us on a personal level. That tendency to think that we knew what was going to happen can play tricks on us and cause us to blame ourselves for things that we could not really foresee. We think we knew what was going to happen, when in reality we did not. When we look at the past with the eyes of the present, the current knowledge often distorts our memory.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)